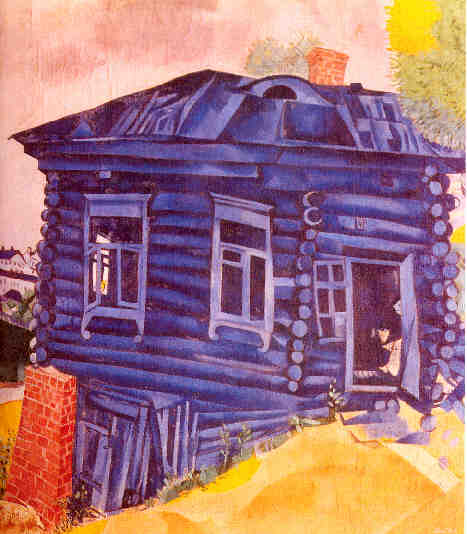

מאַרק שאַגאַל

Hannah's great-grandmother A groyse gedile hot mir getrofn. A big deal it happened to me. I hit the jackpot. Ikh bingeborn gevorn. I got born. In Dvinsk I got born, with the name Leah Alterman, Vulf'sdaughter. Thirty-five versts from Riga we live. The Czar, he owns our land, he tells what we can keep on it, what we can't keep. Just four goats and some chickens means a lot of trouble. The Czar's men come whenever they want, spit on our scholars, take the women to the fields and roll on us, make us dirty like animals, like them. Children give a little bit of joy, sure. But after fourteen winters, I've seen plenty die before they get to their first day of school. Girls we sometimes lose before they can mind the littler ones. Winters are cold, very cold. We have the one stove only, and two beds for all the children, eight of us, plus a little mat made of hay. Because I'm the only girl who lives, I get the mat. Sure, it's hard for me, to be the only girl. Some nights, so cold they are, I bring in a goat to share my mat, keep me warm. My dear father, my tatte, he works in the tannery. He gets a little bit of rubles from it. My brothers go with him, of course. In the summer we sell eggs from our chickens at the market. In the fall we trade our extra for apples. Tatte, he likes my tzimmes, my stew, even without raisins. On Shabbes he takes my brothers to shul, to study Torah with Reb ha-Cohen. Mamme and I, to wash the linens and the clothes, we carry them with the scrubbing board to the lake. In winter, we wash through a hole in the ice. Sometimes on the way back, my brothers' pants turn to ice. A whole verst it is--nearly a mile. We get home, I fork hay to the goats, Mamme starts the cooking. On the string near the stove, I put the laundry to dry. Night and day, we haul water from the cistern out back. To cook and wash the pots for eight people means a lot of buckets. On the days we bathe, vey iz mir. You don't want to hear what I have to say about that. My mother is a shtilinke, a quiet one. Which is to say she doesn't complain much. What else is to talk about, but complaints? She works all the days. She eats a little, she sleeps a little, she goes back to work. She has Shabbes of course. After blessing the candles, she whispers each of our names, so God is reminded of us. So, then she has a day for rest. I think we are a pretty family. Dark eyes we have, dark curls, and sturdy bones. If you take a look behind the eyes, anybody can see, my tatte and my brothers are sharp, good with the books. Me, I am a short girl. But from all the water I haul, I have good muscles--like a donkey. And, when our new goat won't let her baby nurse, I'm the one who clears her teats each morning, and gets the little kid to drink from my bowl. Like I say, I am the only girl who lives. The one before me, Golda, had only two years. The one after my brother Avram, Sora, she lived through a bad, bad winter, then took sick in the spring. She had maybe ten winters, and the best giggle in all of Dvinsk. So, even though I'm a girl, to Mamme, I am a blessing. I am her help. When I am nearly an old maid, nineteen winters, a neighbor girl whose aunt is Yente Malke, she says there's a man with an eye on me. For a few days, while I cook and wash and haul the water, I have little birds in my bosom. Like dreams. I wish for a man with eyes that tell me to him I am beautiful. A man who will buy from the Yiddish book peddler, and read books with me after sunset with help from candles. For this I wish. Then my father tells me, ya, in two weeks I will have a wedding. "Who is it?" I ask him. "Who is it? It is a man," he says. "A good man, a wise scholar. You'll see." Mamme is quiet, quiet. I think, for her this is not so easy. She thinks she will be alone with the work now. "Mamme," I say. "I will live near enough, right? We can still go together to the lake, right? And it will be a while before I have babies. So I can still help you at the market, too." "We'll see," she says. Tatte has left the room. The night before the wedding, Mamme and I are alone, making the challah. Mamme is heavy, sad like the dough after you punch it down. We each braid a long loaf, put them in to bake. Where Tatte usually sits, in our one chair with arms, she sits. So, I sit too. I think, maybe she has a blessing for me. I know talking for her is not easy. So, I wait. My heart feels like a flower, wide open. I wait to hear something nice, something beautiful. But then with a fist she pats her mouth. "Leah, Leah," she says. Little tears come down. "It's Yeshia Zeitlin your father arranged for you to marry. The scholar." I don't know the name. Mamme, she keeps looking at me, not talking. Her eyes are dark like an iron skillet with a thin layer of oil. I smell the challah just then, giving the air a bit of sweet. "Yeshia Zeitlin . . ." I say. With his name on my lips, I recognize. "YESHIA ZEITLIN!?! Yeshia Zeitlin has five children! A widower he is--from a wife dead only two months!" Mamme nods. "The oldest is Tamara, your age. You know her, ya? She'll be your help." My hands, my heart too, they turn to nervous fists. I want to shove Mamme out of Tatte's chair. I am ashamed to say it, but maybe you can understand. I have nothing but a womanish brain after all: I want to shove her out so I can sit in that chair with arms. So if I live twenty years more, at least I'll have this little bit of comfort for my memories. from Katie Singer's novel "The wholeness of a broken heart" Katie Singer family tree Her Great Grandfather on her maternal side was Jacob Usdin |

Vishki was a very small borough bestead by even smaller villages and farms. This is why Jews living in Vishki were craftsmen or owned small shops selling various commodities and first necessity goods. All the Jews spoke Yiddish, most of them Latvian and just a few German or Russian. When I was a kid, I only spoke Yiddish and Latvian. Our family had a house that wasn’t too big, but was newer and better-built then most of the houses in Vishki, with a garden and a vegetable garden in the back yard. My father, Israel Dumesh was a shoe-maker; he was cutting out leather billets for shoes, boots and moccasins for men, women and children. He was working at home, where he had had an equipped workshop and met his clients. My mother, Bluma Dumesh, was a dressmaker; she was sewing dresses and coats. Israel and Bluma always had plenty of work, we weren’t rich but neither were poor and parents always worked very hard to make sure that we (children) have all that we need. But as normal as our life was, I think my father always dreamt of moving from country-side Vishki to a big city like Dvinsk (Daugavpils), Rezekne or even Riga. That’s why when in June 1940 the Reds (Soviet Army) came, he closed his workshop, went to Dvinsk on foot and took a train to Riga to look for a job. There he found a job in a tannery, found a place to rent, and after 4 months came back to Vishki to move the family to Riga. We had spent winter in Riga, fascinated by the beauty of the big city. But after 7 months after our arrival, WWII started; Israel was 36 at that time. Somehow, perhaps from rumors spreading in Jewish neighborhoods, my father knew what would happen to us if Germans were to come. He joined the Workers Guard, an armed civil militia under control of the Red Army, but only because families of the Guardians were subject to evacuation upon demand. On June 22nd war started, and on the 27th June father forced us to take a bus to evacuate to Russia; on our way to the bus we also took my mother’s sister and her 2-year-old daughter. Only 4 days later, on the 1st of July 1941 German forces had entered Riga. Father couldn’t evacuate, stayed in Riga and was sent to the Ghetto. But he was a working man with skillful hands; Germans were using people like this for work. When in November 1st mass executions had started, he among about a hundred other Jews was transferred to Mezhapark (woods close to Riga, where a concentration camp Kaisenwald was located). He stayed there until October 1943, when together with war prisoners they were taken to Germany by Baltic Sea in big barges. He then was imprisoned in a concentration camp by Stuttgart, which in March 1945 was liberated by the Soviet soldiers. Many survivor Jews after liberation hurried back home, but my father again proved to be a wise man and took a moment to think the situation over. Latvia by that time was already under a Soviet Occupation, Stalinist repressions and ethnic cleanings were raging. Any war prisoner that had survived German captivity was treated as a traitor, who "supposedly" collaborated with Nazis in exchange for their life. Same judgment applied to Jews who got through concentration camps alive, many of them were imprisoned and deported to Siberia without any investigation or trial. To avoid such a faith, Israel joined Red Army and was fighting against the Nazis up until the end of the war when he was demobilized and returned to Riga as a hero and a liberator. He was even conferred a decoration upon the "Victory over Germany". When my father returned to Riga, he found us right away; we have returned from evacuation by that time and were staying with some friends of my mother, where in a room of 20 square meters about 15 people were sleeping. We were granted an apartment in the centre of the city, and a normal life finally started. I went to school, before that I had only learned for one year in Hedera in Vishki. Father never spoke about what he had experienced during the war, all the horrors of ghetto, concentration camps, death and famine. He always said that knowing that he had saved his family was the only thing that was keeping his heart warm. But as all Holocaust survivors, he had had a deep psychological trauma for the rest of his life. After returning to Riga, father had opened a small shoe-making workshop in the center of the city. He was managing the workshop, there were 3 other shoe-makers working with him, all Jews. They were doing pretty good. Father spoke Russian pretty well, but his written Russian wasn’t so good, so I was helping him out with book keeping. His workshop was working until 1951, when my father’s unique ability to foresee dangers worked again. In the early 50’s Soviet Union started to fiercely eliminate any kind of private ownership; many entrepreneurs, partnerships and enterprises were nationalized and its managers often imprisoned or deported. Same faith would await Israel also, hadn’t he closed his workshop and moved to work for a state-owned shoe factory. He was working there for 25 years, had made a good career from a simple worker to the head of one of the production units and retired in 1974. That’s in short about my father Israel Dumesh. I have always been very proud of him; he was a strong man who went through a lot in order not to perish and save his family. A real hard worker respected in the community and loved by the closed ones. Told by Leizer Dumesh, recorded and translated by Vadim Dumesh .Dumes site in Bruce writes: " As it turns out, not all the Dumesh families were related, as can be the case where the surname comes from a place name. According to Alexander Beider in A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Russian Empire, the name "Dumes" and "Dumesh" were from the village of Domashi, about 35 miles from Višķi in what is now Belarus. We have verified this by DNA tests between Bruce Dumes and Vadim Dumesh, great-great-grandson of Genoch, listed in the 1897 census."

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I can't resist to place here a Jewishgeners dialog in may 2007:

Mark S... asked: "While searching for my relation, Abraham K...in the

ANSWERS: May be it was a transliteration of Katske, it is Polish (and also used in Yiddish)

And why not? Cats (and dogs) both eat meat and I doubt that canned or

Somebody's got to do it. And for a widow, a godsend. We came to the UK from

British readers of a certain age are likely to remember Matthew Mugg, a friend of

"The cat's-meat-man used to make a business of rat-catching for the

Thanks to all who replied to my inquiry regarding whatI thought was an odd

|

Finally I’m writing to you about my Uncle Moisey and how he helped us during the WWII. Leizer Dumesh (photo taken by Bruce in Riga.August 25,2007)

|